| The PDF Version |

|

CONTACT: snaranan@gmail.com Tel: 91-44-24513441 ADDRESS: 67, 19th Street Venkateswara Nagar Kottivakkam Chennai 600041, INDIA |

© Copyright 2011

Prof. S. Naranan

Chennai 600041, INDIA

|

MARTIN GARDNER

(1914-2010)

Martin Gardner is an iconic polymath with extraordinary learning, spanning Philosophy, Metaphysics, Science (Mathematics and Physics), Recreational Mathematics, games, puzzles, magic tricks and art. He is best known for his series of columns “Mathematical Games” that appeared in Scientific American for 25 years during 1956-1981. There are 330 columns, reprinted in 15 volumes, in several editions with updates. They define “Mathematical Recreations”, a genre of Mathematics he created all by himself.

Gardner gave up writing in Scientific American, perhaps because it left little time for writing about his other variegated interests. He was active and publishing books until his death in 2010 at age 95. In all he wrote more than 100 books, the last one in 2009 to mark his 95th birthday. A list of his writings – columns, articles, reviews and books – runs to a few hundred pages.

It is said that Gardner never used computers and used only a typewriter for all his writing and correspondence with a large network of his readers and admirers. Long before the present-day Internet ‘blog’, Gardner innovated exchange of letters with hundreds of his readers consisting of mathematicians, computer scientists and programmers and puzzle-lovers to make his columns interactive. Based on feedback from readers, he published updates on solutions to the Mathematics problems in his columns and new editions of his books. It is reported that he spent a whole day every week on correspondence, which he typed standing in front of an old typewriter mounted on a pedestal.

Martin Gardner’s mathematical education was only up to high school. He got a B.A. in Philosophy from the University of Chicago in 1936. He dropped out of graduate study in the first year. Some believe, this lacuna may have had an advantage. Gardner is reported to have said that if something was not clear to him, it will most probably be unclear to many of his readers. His intellectual integrity made him check out many facts with “original sources” and double check all he wrote. Perhaps that accounts for the extraordinary clarity of his writing, reflecting similar clarity in his thinking.

The Scientific American columns spawned an ever-growing community of laymen-turned-mathematicians. At the same time thousands of mathematicians turned puzzle-lovers. There is a subtle distinction between Mathematical Recreations and Recreational Mathematics. In Mathematical Recreations, the emphasis in on the puzzles (games, magic tricks), based on mathematical principles. Most of them are Gardner’s creations. In Recreational Mathematics, key mathematical ideas – some very abstract – are unraveled by lucid exposition to lay readers. Gardner excelled in both. In early 1970’s, Donald E. Knuth, published the book “Fundamental Algorithms”. It was the first of six volumes planned, covering algorithms for computation, meant mostly for undergraduates in Computer Science. A large part of the book was devoted to problems. Gardner discovered that many of the problems could be adapted for Recreational Mathematics. Many readers turned avid computer programmers.

Gardner revealed many new important advances in Computer Science for the first time in his Scientific American columns. Here are a few examples. Gardner introduced the “Game of Life” of the famous mathematician John Conway, a game with applications in ‘cellular automata’. In 1977, Ronald Rivest of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T), Cambridge (U.S.A) – one of the famous trio ‘Rivest, Shamir and Adelman’– approached Gardner offering to reveal for the first time to the public, the path-breaking ‘RSA’ algorithm based on trap-door ciphers. It made possible secret and private communication on a public channel like the Internet. Such a move was strongly resisted by the National Security Agency (NSA) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the U.S. Govt. But Gardner could not refuse Rivest’s offer and published the RSA algorithm in the August 1977 issue of Scientific American. Although brief, the revealed algorithm could be easily implemented in Fortran code by anyone with knowledge of elementary Number Theory. This was perhaps the ‘greatest coup’ in Gardner’s lifetime. Gardner popularized ‘Fractals’ discovered by Benoit Mandelbrot. Fractals had links with the beautiful Mandelbrot set, order and chaos in complex systems (non-linear dynamics). They were highlighted in a column in 1983. Fractals, perhaps more than any other concept, brings out the strong links between Art and Mathematics with the aid of powerful computers.

Perhaps because of his university education in philosophy, Gardner had an abiding interest in metaphysics and religion. Yet he was a champion of the scientific method – “defending reason, attacking fraud” – and a founder of the modern skeptic movement.

Gardner’s seminal role in propagating Mathematics and Mathematics Education is recognized by a commemorative book “The Colossal Book of Mathematics” published in 2002. Note that the compilation stressed Mathematics rather than the puzzles. This is remarkable for a mathematician who probably never studied calculus.

What was Gardner’s first publication? Gardner was the editor of a children’s magazine “Humpty Dumpty” and he designed ‘paper-folding puzzles’ for the magazine. They caught the attention of Scientific American, and led to the first article by Gardner in the magazine: ‘Hexaflexagons’. Soon after, began the regular columns on MG (Mathematical Games!) by MG starting from January 1957 that entertained the readers for 25 years. The rest is history. Today we remain grateful not only to Martin Gardner for the bounty he created in Recreational Mathematics but also to Scientific American for popularizing it.I had the luxury of a personal subscription to Scientific American from 1957 for several years. It was a gift from my brother-in-law Dr. S. Ramachandran who lived in the U.S. When the monthly magazine arrived, I would skip its contents to go to Gardner’s column. So, I was hooked to it from very early days. Around early 1960’s, I wrote a letter to Martin Gardner after reading his column on Mathematical Billiards (Bouncing balls in polygons and polyhedrons). I pointed out a similarity between one of the billiard ball trajectories and a ‘kolam’ design. Kolam is a closed curve meandering through the gaps in a rectangular grid of dots, a folk-art popular in South India. Gardner replied immediately, saying he will comment upon it in a future updated version, when it happens.

I found the August 1977 article on trap-door ciphers and the revolutionary RSA algorithm, mentioned earlier, fascinating because of its connection to Number Theory and Prime Numbers. The RSA algorithm for secure communication is based on the fact that while it is easy to create large prime numbers (say 100 digits), it is very difficult to factorize a large number (say 200 digits) into its two large prime factors (each 100 digit). To me it was incredible that such an algorithm could be invented in cryptography. I was spurred to write the RSA code with the help of a programmer colleague. After nearly 35 years, the RSA code remains the workhorse of secure communication on the Internet. The article on Fractals in 1983 led me to a life-long interest in non-linear dynamics, order and chaos in complex systems. In short, Martin Gardner was responsible for broadening my interests beyond Physics and Astronomy, to Mathematics, Statistics, Number Theory, Cryptography, Computer Science, Complex systems, and Quantitative Linguistics.

In 2007, I wrote an article in two parts titled “Kolam Designs Based on Fibonacci Numbers”. I found a new modular approach to build kolam designs of any arbitrary size and shape using some unique properties of Fibonacci Numbers.

It was my brother S. Srinivasan (“Seenu”) of Austin, TX, who suggested the idea to write to Martin Gardner about my kolam work, especially because I had a brief correspondence with him about 50 years ago! The hard copy of the article had to be sent by post. Seenu, after some effort, succeeded in finding the postal address. The subsequent events are described in Seenu’s words:

“.....Nannu’s (S. Naranan’s) cover letter was dated 16 April 2010. I signed his name and posted the package on the 19th. Mr. Gardner received it on the 21st, his reply was dated 22nd and he mailed it on 23rd. Nannu received it on the 30th April – all within 11 days. Sadly on Monday, May 22, 2010, Mr. Gardner passed away, a month after writing to Nannu”.

I acknowledged Gardner’s letter and posted it on 1 May 2010. I wrote:

“... I am overwhelmed by your acclaim of the paper as “beautiful” and worthy of publication. You have deemed the work fit for a whole “Martin Gardner Scientific American” column. There can be no higher commendation of its worth. I say this because every one of the 300 columns you wrote in the Scientific American is a classic today that is still reprinted and reissued in new editions.

... I note that you assessed the value of my papers, wrote the reply and mailed it by post, all in less than 24 hours after receiving my articles by post. This meant lot of time and effort. I am very grateful for your kindness”.

Looking back at the sequence of events, I recall that for nearly three years I hesitated to write to Martin Gardner. On 16 April 2010, one day before I completed 80 years, I thought I should do something worthwhile. On the spur of the moment I wrote the letter. I was unprepared for the laudatory reply so promptly written by Gardner. I am grateful to my brother Seenu for being instrumental in getting my kolam work into the hands of Gardner. My letters of 16 April and 1 May and Gardner’s letter of 22 April 2010 are reproduced below as items 1, 2 and 3.

1. My first letter to Martin Gardner dated 16 April, 2010:

Prof. S. Naranan 16 April 2010 20 A/3 Second Cross Street Jayaramnagar Thiruvanmiyur CHENNAI 600-041 (India). Dr. Martin Gardner Windsor Gardens, Room 216 750 Canadian Trails Drive NORMAN OK 73072 U.S.A. (405) 329 8845. Dear Dr. Martin Gardner, I am a professor of Physics (Astronomy and Astrophysics) and retired from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (Bombay) after 42 years of research (1952-1992). I will be completing 80 years tomorrow. Recreational mathematics was my hobby from my young days and I was a regular reader of your columns in the Scientific American (1956-1981). They were the inspiration for my efforts to diversify my interests to other areas such as mathematics (number theory, statistics), cryptography, statistical linguistics, complexity theory etc. In 2007 I wrote a paper (in two parts) on “KOLAM DESIGNS BASED ON FIBONACCI NUMBERS”. The best way to introduce the topic is the brief abstract of the paper, reproduced below:

About 50 years ago (early 1960’s), after reading your column on Mathematical Billiards (Bouncing balls in polygons and polyhedrons) I had written a letter to you about the similarity between a kolam design and a billiard ball trajectory (Fig 1(j) in Part I). You had kindly responded that you will comment on it if you had another occasion to dwell on the subject. Now, I have taken the liberty to encroach on your precious time by writing this letter enclosing the paper on Fibonacci Kolams. It is available on the internet: http://vindhiya.com/Naranan/Fibonacci-Kolams/ There is also a set of “special kolams” besides the paper. The website has a slide show on Fibonacci Numbers and Fibonacci Kolams in PowerPoint. The connection between kolam designs and Fibonacci Numbers that I have exploited is indeed very simple. If (a,b,c,d) are four consecutive integers of a Generalized Fibonacci Series (c = a+b, d = c+b) , then d2 = a2 + 4 b c The geometrical interpretation of the above equation is: a square of side d contains a smaller square of side a at the center with the remaining space filled by four rectangles b x c; each rectangle is rotated by 90o with respect to its adjacent one (Fig 2 of Part I). This geometrical interpretation has not been dealt often in the immense literature on Fibonacci Numbers. The paper deals only with square and rectangular kolams (of any arbitrary size) but it is possible to generate kolams of arbitrary shape too, simply by using the squares and rectangles as modules. I have indeed, a collection of kolams of different geometrical shapes. Recently I completed a paper on “Statistical Analysis of Failures in Solving Crossword Puzzles”. I used 10 years of data on the number of my failures in solving crossword puzzles. I found that the distribution of the number of failures is a very good fit to the Negative Binomial Distribution. I believe, this is the first instance of a study of failures in solutions of crossword puzzles. The paper will be published shortly in the Journal of Quantitative Linguistics. I am mentioning this since crossword puzzles are the most popular linguistic puzzles. I read recently that you completed 95 years and marked the occasion by publishing yet another book. I wish you many more years of healthy and active life. You are and will continue to be an inspiration to all. Warm regards. Sincerely, P.S. This letter and the contents are being mailed to you my brother Mr. S. Srinivasan who lives in Austin, TX. P.S. (added on 4 May 2010) There was a serious error in the equation in para 2 of page 2 in the version sent to MG. d and a were interchanged. The correct equation is: d2 = a2 + 4 b c.

|

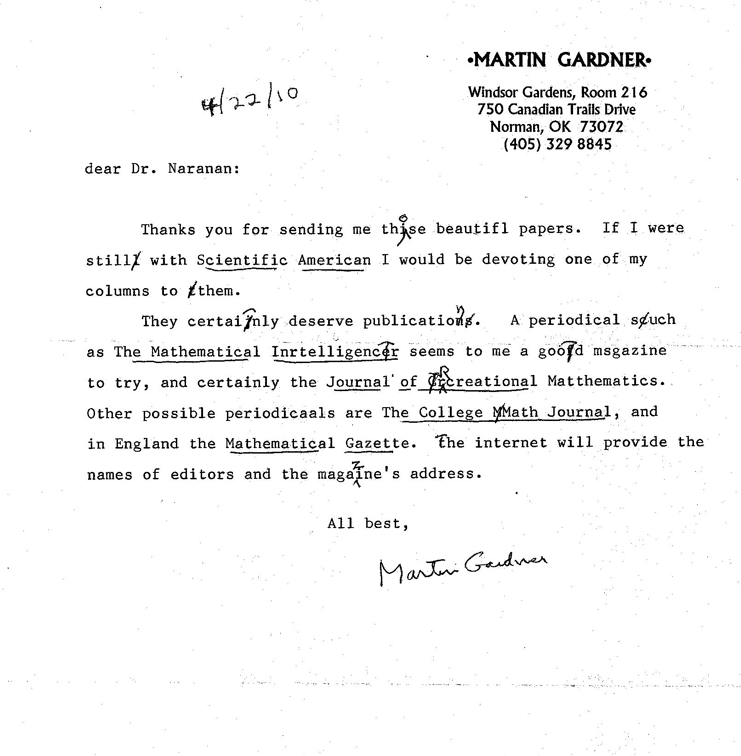

2. On April 30, 2010, I was delighted to receive this typed letter from Mr. Gardner.

|

3. My response to Martin Gardner on 1 May, 2010:

Prof. S. Naranan 1 May 2010 20 A/3 Second Cross Street Jayaramnagar Thiruvanmiyur CHENNAI 600-041 (India). Dr. Martin Gardner Windsor Gardens, Room 216 750 Canadian Trails Drive NORMAN OK 73072 U.S.A. (405) 329 8845. Dear Dr. Martin Gardner, Thank you for your reply dated 22 April 2010 to my letter of 16 April, enclosing my article KOLAM DESIGNS BASED ON FIBONACCI NUMBERS. I received your reply yesterday. I am overwhelmed by your acclaim of the papers as “beautiful” and worthy of publication. You have deemed the work fit for a whole “Martin Gardner Scientific American Column”. There can be no higher commendation of its worth. I say this because every one of the 300 columns you wrote in the Scientific American is a classic today that is still reprinted and re-issued in new editions. I am familiar with the names of the journals you suggest that may be willing to publish my work. The best bet is the Mathematical Intelligencer, which devotes substantial space to “Fun Maths”. But it means drastically abridging and rewriting my articles. Meanwhile, the website of my articles on the internet http://vindhiya.com/Naranan/Fibonacci-Kolams/ is getting some exposure and I am hoping that it will increase in time. I note that you assessed the value of my papers, wrote the reply and mailed it by post, all in less than 24 hours after your receiving my articles by post. This meant lot of time and effort. I am very grateful for your kindness. I wish you many more years of intellectually active and healthy life. Best regards Sincerely (S. NARANAN)

|

Sadly Martin Gardner passed away on May 22, 2010 at age 95, within weeks of reviewing and commenting on my paper.

S. Naranan,

Chennai, India

June 27, 2012